A few weeks ago Northern California was rocked by huge power outages which PG&E hoped would prevent wildfires ignited by tree limbs falling on power lines. At the time weather conditions included heavy wind storms, drying out an already extremely dry landscape, raising the fire danger high enough to make regulators nervous. PG&E claims the power outages prevented some wildfires, but they did not stop all the wildfires, and in late October 2019 it seemed the whole area was on fire. Still the power outages caught our collective attention, and one solution bandied about is that “microgrids” could keep the power on even if PG&E has to shut down power lines over a broad area.

The general problem is bigger than what Northern California faced during October 2019. Southern California had its own terror period with dozens of wildfires, many of which were ignited by tree limbs falling on power lines. And at the time of this writing, Australia is facing truly catastrophic fire dangers. The city of Sydney is surrounded by massive fires, hundreds of homes have already been destroyed, and tens of thousands other homes are at risk. In other areas hurricanes in recent years have forced prolonged power outages.

The common thread is climate change. Climate scientists have long predicted an increase in extreme weather conditions. Extreme weather conditions in turn will interrupt the electricity grid, where in some places the utility companies will shut off the grid to avoid fire risk, or in other cases widespread extreme storms will bring down power lines over a large area.

Enter the Microgrid, promising a solution

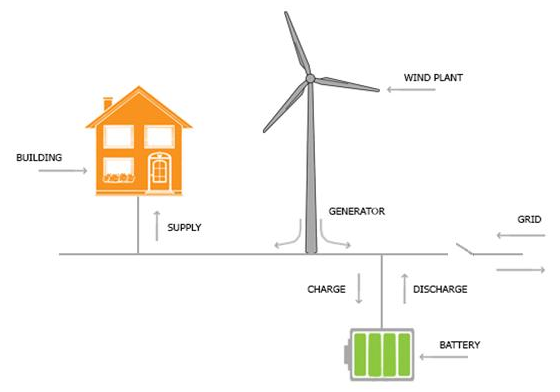

Microgrids are localized power grids that can operate independently from the main, centralized grid. The area served by a microgrid can continue to function even if the main electricity grid goes down.

The electricity serving a microgrid doesn’t magically appear. Instead a microgrid exists within defined electrical boundaries within the overall electrical grid, has the ability to disconnect itself from the main electrical grid, and has local energy resources. The local energy resources are called distributed energy resources (DER), and disconnecting a microgrid disconnects from the grid is called islanding.

For example, in July 2019 Bloom Energy (a maker of grid-scale fuel cell systems) reported![]() on power issues at Home Depot stores in New York State. A heat wave and extreme storms cut off electricity to hundreds of thousands of electricity customers in New York and New Jersey. Six Home Depot stores rode through the power outages thanks to their Bloom Energy microgrid systems. The stores in question saw outages for as much as six hours at a time. The Bloom Energy fuel cell has the ability to operate as a microgrid, meaning that each affected Home Depot store was taken off the grid by the fuel cell unit and every function of the store was able to continue, with the benefit to Home Depot being that the store continued making sales.

on power issues at Home Depot stores in New York State. A heat wave and extreme storms cut off electricity to hundreds of thousands of electricity customers in New York and New Jersey. Six Home Depot stores rode through the power outages thanks to their Bloom Energy microgrid systems. The stores in question saw outages for as much as six hours at a time. The Bloom Energy fuel cell has the ability to operate as a microgrid, meaning that each affected Home Depot store was taken off the grid by the fuel cell unit and every function of the store was able to continue, with the benefit to Home Depot being that the store continued making sales.

In this case the defined electrical boundary for the microgrid was each Home Depot store.

A single family home with a simple solar panel array does not by itself constitute a microgrid. Most solar arrays are designed to shut down if the electric grid shuts down, because of the risk of electrocuting power company line workers. Instead the solar array needs to be accompanied by an energy storage unit (e.g. the “Power Wall” product by Tesla) and the system requires a solar inverter with the capability to island itself from the main electric grid.

Another model is a campus, like Las Positas College (a community college outside Livermore CA). In 2015, Las Positas announced![]() they’d install a large energy storage system (1 megaWatt-hour) to accompany the 2.5 megaWatt solar array on the campus. In normal operations the goal is to self-generate most of the electricity consumed on the campus – over 435,000 square feet of offices and classrooms over several buildings. They expect over $75,000 per year in electricity cost savings, and the system is meant to island itself from the main electricity grid.

they’d install a large energy storage system (1 megaWatt-hour) to accompany the 2.5 megaWatt solar array on the campus. In normal operations the goal is to self-generate most of the electricity consumed on the campus – over 435,000 square feet of offices and classrooms over several buildings. They expect over $75,000 per year in electricity cost savings, and the system is meant to island itself from the main electricity grid.

In other words, a microgrid can serve any sort of facility from a single family home, to a big-box retail store, to a campus. What’s needed is to define the boundary of the microgrid. Usually there is a single Point of Common Coupling (PCC) where there the electrical service of that defined boundary is connected to the electric grid.

During normal operations a microgrid can store self-generated electricity locally, for local consumption rather than selling the electricity to the grid. It’s during abnormal operations, when the main electric grid goes down, that folks hope that microgrids can prevent power outages.

The problem seen is wildfire risk in rural areas during certain time. The proposed solution is to shut down rural electrical service in such times. The question is how do individual electricity consumers continue having electricity at such times?

PG&E looking to develop microgrids

According to Microgrid Knowledge![]() , during a meeting with the California Public Utilities Commission, PG&E CEO William Johnson told the commission “There is a definite need to move toward some form of microgrid sectionalization.” What that means is the development of “resilience zones,” which are subsections of the electric grid that are configured to convert into a microgrid. There will be local electrical generation capacity to continue supplying electricity to a given locale.

, during a meeting with the California Public Utilities Commission, PG&E CEO William Johnson told the commission “There is a definite need to move toward some form of microgrid sectionalization.” What that means is the development of “resilience zones,” which are subsections of the electric grid that are configured to convert into a microgrid. There will be local electrical generation capacity to continue supplying electricity to a given locale.

This would be a different sort of microgrid than just discussed. For example a small town could be “sectionalized” away from the main electricity grid. If you’re like me, this is the first time you’re seeing this word. From the discussion it sounds like “sectionalizing” means sort of what it sounds like, which is to divide the electric grid into independent sections when normally the grid is all interconnected.

San Jose looks to end its relationship with PG&E

In another Microgrid Knoweldge![]() article, it’s noted that the Mayor of San Jose California (in the heart of Silicon Valley), wants to divorce itself from PG&E and to develop microgrids for local resilience. Mayor Sam Liccardo noted that PG&E has made it clear that we should expect widespread power outages in the future. If nothing else, PG&E’s plan will take 10 years to implement.

article, it’s noted that the Mayor of San Jose California (in the heart of Silicon Valley), wants to divorce itself from PG&E and to develop microgrids for local resilience. Mayor Sam Liccardo noted that PG&E has made it clear that we should expect widespread power outages in the future. If nothing else, PG&E’s plan will take 10 years to implement.

The Mayor said the most feasible long-term solution “lies in distributed, off-grid electricity generation, and storage, which can take several forms. Enabling residents with solar arrays to create islands of resiliency within neighborhoods can help, as can investing in larger microgrids in strategic parts of the city.”

The plan is for San Jose to form a Municipal Utility, and to develop several forms of neighborhood-level energy resiliency.

Not so fast, says a utility company representative

In late October 2019 – in the midst of California’s wild wildfire season, when the whole state seemed to be on fire – Scott Aaronson of the Edison Electric Institute wrote on Utility Dive a caution that Microgrids alone cannot eliminate wildfire risk![]() . EEI is a trade organization representing the “Investor-owned Utilities” in the USA.

. EEI is a trade organization representing the “Investor-owned Utilities” in the USA.

Aaronson claims that in the face of risks due to the existence of the electric grid, “One suggestion has been to do away with the interconnected energy grid and rely instead on microgrids.” In other words, he claims the suggestion is to eliminate the main electricity grid, and instead have everyone using microgrids. I don’t know how accurate that is. If nothing else, the microgrids I’m aware of are all connected to the main electricity grid.

A microgrid is more expensive to build. At the level of a single family home, the minimum cost system is the service panel and its connection to the grid. Installing a microgrid for that single family home requires a solar array, a solar inverter with islanding capability, and an energy storage unit. Those items must be sized correctly to handle not only daily electricity needs, but to handle a day or two of power outages. It’s not rocket science to design such a system, I learned how to calculate the numbers a couple years ago and learned that the calculations are well known and understood. The point is you’re talking about $10-20,000 worth of equipment, for a single family home.

Not every family owning such a home can afford that expense. Not every single family home is in a position to make use of solar power. Not every family lives in a single family home – so a solution would have to be developed for electrical supply at apartment complexes. Not every apartment complex is in a position to make use of solar power. In other words, not every electricity consumer has the ability to self-generate electricity on-site with renewable energy systems.

Getting back to Aaronson’s article – we see him say “the grid’s interconnectedness allows electric companies to leverage a broad set of tools, characteristics and capabilities that enhance resilience in ways that a self-contained microgrid cannot.”

His job with the Edison Electric Institute is to represent the interests of utility companies. So we have to take what he says with a grain of salt. However, he makes a very good point. The electricity grid is extremely useful to everyone. It provides a backbone across which electricity can be shared between a variety of electricity producers and electricity consumers.

Aaronson see’s “the capability to island off sections of the energy grid during emergency situations” as “one tool in the toolbox for electric companies”. What he’s referring to is plans underway for the ability to orchestrate the electrical consumption and generation across a range of distributed energy resources across the electric grid.

That goal is for the individual energy systems – solar array on a home, up to a campus-level energy system – to have local computing capability. It would be capable of receiving commands from the utility company, to schedule electricity consumption or generation based on needs the electric grid. Supposedly the owners of such distributed energy resources will make money from offering these grid energy services.

Bottom line is – Scott Aaronson, the representative of the utility companies, spins a very good tale about the value of the electricity grid. His suggestion is to not throw the baby out with the bath water, meaning don’t switch whole-hog to the microgrid idea and completely eliminate the main electricity grid. The rationale is sound, since the electricity grid does offer value to society as a whole.

- Is there enough Grid Capacity for Hydrogen Fuel Cell or Battery Electric cars? - April 23, 2023

- Is Tesla finagling to grab federal NEVI dollars for Supercharger network? - November 15, 2022

- Tesla announces the North American Charging Standard charging connector - November 11, 2022

- Lightning Motorcycles adopts Silicon battery, 5 minute charge time gives 135 miles range - November 9, 2022

- Tesla Autopilot under US Dept of Transportation scrutiny - June 13, 2022

- Spectacular CNG bus fire misrepresented as EV bus fire - April 21, 2022

- Moldova, Ukraine, Georgia, Russia, and the European Energy Crisis - December 21, 2021

- Li-Bridge leading the USA across lithium battery chasm - October 29, 2021

- USA increasing domestic lithium battery research and manufacturing - October 28, 2021

- Electrify America building USA/Canada-wide EV charging network - October 27, 2021