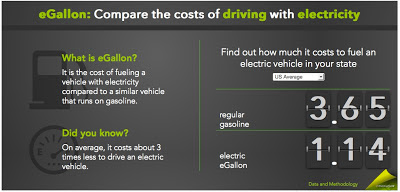

On Tuesday the US Dept. of Energy unveiled the eGallon, in an attempt to dispel some confusion about the cost of operating an electric or gasoline powered car. Many are reacting to the high price of gasoline by looking for alternatives, but then get lost in the question whether the electric car will save enough money to pay for the higher up-front price. The eGallon is an interesting idea, and uses a model for operational cost that I (and others) have written about before. Unfortunately the Dept of Energy’s presentation of the eGallon idea is flawed and doesn’t help much.

This is what visitors to the DOE eGallon web page![]() find. An overly simplistic calculator, and I can hear the questions about the ultra-low price for driving on electricity. The ideas behind eGallon are sound, but the presentation falls into that category where people say “extraordinary claims require extraordinary proof.”

find. An overly simplistic calculator, and I can hear the questions about the ultra-low price for driving on electricity. The ideas behind eGallon are sound, but the presentation falls into that category where people say “extraordinary claims require extraordinary proof.”

Another thing that the DOE eGallon page does not make plainly clear is that it’s showing the cost savings for driving electric. The information to reach that conclusion is here on the page, but worded and presented in an unclear way. For example, there could be a third row to the numbers showing the cost savings.

If you click through the “Data and Methodology” link in the fine print at the bottom of the page, we eventually find out how these numbers are calculated.

For example:

How is eGallon calculated?

To determine the eGallon price for each state, the Department of

Energy calculates how much electricity the most popular electric

vehicles would require to travel the same distance as similar models of

gasoline-fueled vehicles would travel on a gallon of gasoline. That

amount of electricity is then multiplied by the average cost of

electricity for the state. This gives consumers a clear comparison of

the cost of driving on electricity vs. a similar sized car that uses

gasoline.

Even this, while a better explanation, doesn’t help us understand precisely what’s going on. The model they’re talking about is one I and others have written about before. (see Why electric cars are cheaper to drive than gasoline cars![]() )

)

The model focuses solely on fuel costs and does not cover the full lifecycle cost of ownership. There are a lot of cost savings from electric vehicle ownership that are not covered by fuel cost savings. For example, the smaller maintenance costs (no oil changes, fewer brake pad changes, etc) are not represented by fuel cost savings.

In any case the nice paragraph above doesn’t satisfy me, because I want to understand how they came up with these numbers. Clicking through the links offering to explain the methodology, and we finally come to this little paper: http://energy.gov/sites/prod/files/2013/06/f1/eGallon-methodology-final.pdf![]()

It describes this formula:

eGallon ($/gal) = FE * EC * EP

Where

FE = the average comparable passenger car adjusted combined fuel economy, miles/gallon

EC = the average electricity consumption (kWh/mi) of the top 5 selling PEVs in the U.S.

EP = the average U.S. electricity price, $/kWh.

This presentation of the formula tries to generate a nationwide average. However it’s possible to use this formula to calculate the eGallon for a specific electric car, in comparison to a specific gasoline car, based on a specific price for electricity:

FE = fuel economy of an equivalent gasoline car for comparison (miles/gallon)

EC = electricity consumption (kilowatt-hours/mile) for an electric car

EP = electricity price ($/kilowatt-hour)

This is an interesting formula to think about, and could serve as a tool for comparing different cars with each other.

But the DOE website misses the opportunity to do so and instead leaves the visitor wondering where this magic number is coming from. I suspect some right winger will seize on this as more proof that the Obama Administration is engaging in social engineering and cherry picking numbers out of thin air to make a case for electric cars.

Instead of that, the DOE website could have been educational about costs and benefits for adopting electric vehicles.

- Highway design could decrease death and injury risk, if “we” chose smarter designs - March 28, 2015

- GM really did trademark “range anxiety”, only later to abandon that mark - March 25, 2015

- US Government releases new regulations on hydraulic fracturing, that some call “toothless” - March 20, 2015

- Tesla Motors magic pill to solve range anxiety doesn’t quite instill range confidence - March 19, 2015

- Update on Galena IL oil train – 21 cars involved, which were the supposedly safer CP1232 design - March 7, 2015

- Another oil bomb train – why are they shipping crude oil by train? – Symptoms of fossil fuel addiction - March 6, 2015

- Chevron relinquishes fracking in Romania, as part of broader pull-out from Eastern European fracking operations - February 22, 2015

- Answer anti- electric car articles with truth and pride – truth outshines all distortions - February 19, 2015

- Apple taking big risk on developing a car? Please, Apple, don’t go there! - February 16, 2015

- Toyota, Nissan, Honda working on Japanese fuel cell infrastructure for Japanese government - February 12, 2015