Electric Last Mile Solutions is offering the only Class 1 fully electric delivery van, and hopes its operational cost advantage will turn into a volume of 80,000 units per year by 2025. Going by the name they’ve given the company, the focus is on urban delivery vans such as are used by small shops or mega-sized delivery companies.

The company is setting up manufacturing in the former Hummer plant in Mishawaka, Indiana. With that 675,000 square foot factory, Electric Last Mile Solutions (ELMS) plans to go big specifically in the electric delivery van market. The goal is for the factory to be 90% ready with a trained workforce of 400 employees by Q3 2021.

While ELMS is a brand new company, launched in late 2020, its staff have decades of industry experience, and the company is directly derived from an earlier company. The precursor company, most recently called Seres, and previously SF Motors, had previously intended to sell an electric car. But in mid-2019 the company had a slowdown, and laid its off employees.

Further, ELMS has partnered with Chinese vehicle and battery makers allowing them to quickly bootstrap. The van is sourced from an existing delivery van manufactured by Sokon, which is claimed to have been the top-selling commercial delivery van in 2020. Seres (and SF Motors) were also partnered with Sokon. The drive train is sourced from a “domestic” (USA, presumably) supplier, and the battery packs come from CATL, a Chinese battery maker.

ELMS makes a compelling case that they can launch operations at a lower cost of entry than can the companies which started from scratch. But the key to success is whether the company can deliver, at scale, a reliable van that hits the total cost of ownership gains they claim.

There is stiff competition forming around electric commercial trucks. In a slide deck shown to investors, ELMS names Rivian, Workhorse, Ford, General Motors, and Canoo as competitors. One distinction ELMS has is theirs is the only offering in the “Class 1” (under 6,000 lb) range. The others are offering Class 2 vehicles, in the 10,000-14,000 lb range. This means ELMS will naturally compete in a slightly different space, and contribute to their cost advantage.

The company claims to have 30,000 pre-orders, and lists several companies as either having placed orders, or they are in discussions. These companies include Walmart, Cox Automotive, Ryder, Best Buy, Merchants Fleet, Randy Marion, Ikea, and Donlen.

Preparing ELMS for production

Launching the manufacturing plant is expected to require a fraction of the investment for competing companies. It’s expensive to start a full vehicle manufacturing company, where $2 billion of investment is barely enough to get a company started. By reusing a vehicle design from China, ELMS hopes to get started with a few hundred million in investment.

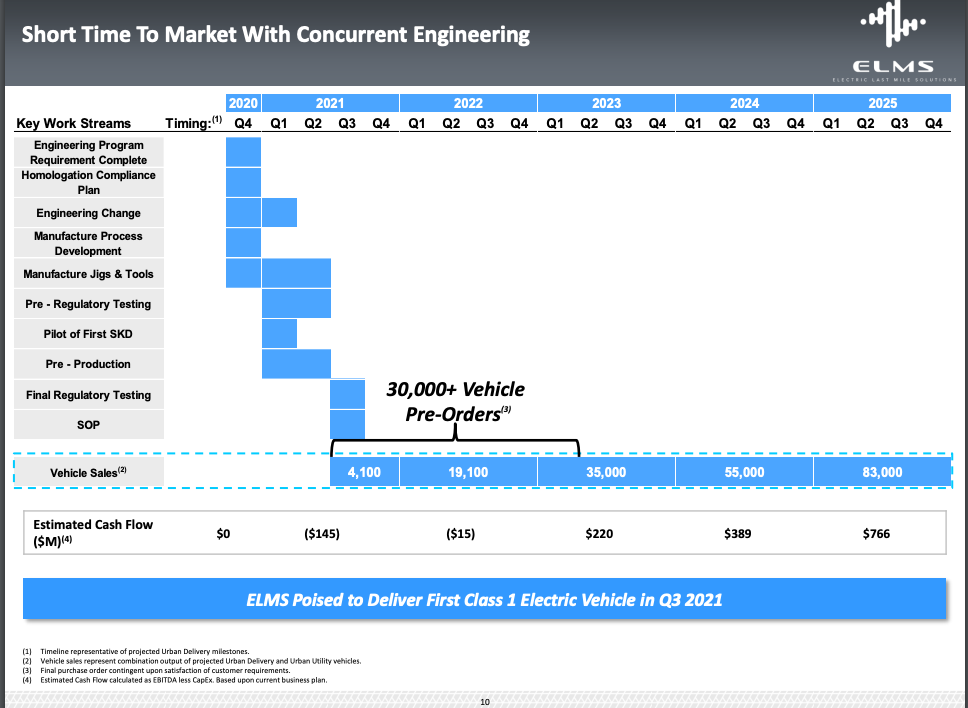

The delivery/manufacturing timeline is aggressive:

Namely, the intention is to build a few thousand vehicles in the latter part of 2021, then by 2023 to be building (and selling) 35,000 vehicles per year, at which point they’ll have $220 million cash flow.

Operational Costs for electric trucks

What will drive interest in their product offering? Operational cost reductions.

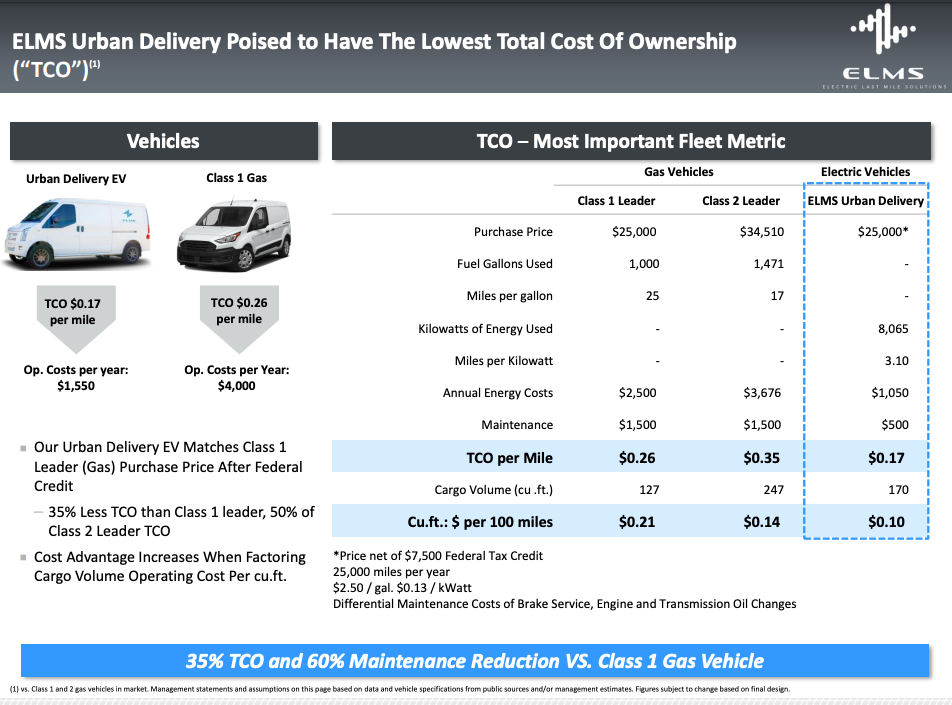

The base price for ELMS’s van is expected to be about $25,000, which is in line with other delivery vans like the Ford Transit Connect. An advantage is the ELMS van will have 35% more cargo space than for competitors.

This is where the investor slide deck outlines the operational cost reductions. You can tell this slide deck was created by marketers because the units are incorrect. Where it says “Kilowatts”, it should read “KiloWatt-Hours”. But, really, let’s not get distracted by that.

The point is that electricity is a cheaper fuel than diesel or gasoline. Further, maintenance costs are lower for an EV than for a gasoline or diesel vehicle. That translates into a drastically lower operational cost. This should get the attention of any delivery company.

This is exactly what I’ve been told by delivery company management on this issue. That a company like Frito-Lay didn’t buy a bunch of trucks from Smith EV for altruistic reasons. They saw the potential to save gobs of money on operational cost savings.

An example is the number of required shop visits per year. Gasoline or diesel trucks must go into the shop at least 4 times per year if only to replace the spark plugs and change the oil. With an electric van, there are no spark plugs or oil to replace, allowing 2 or 3 shop visits per year. That avoids maintenance cost and improves the utilization of the vehicles. Another cost reduction is in brake pads because regenerative braking means less brake pad wear.

Historical validation of lower operational costs

A hundred years ago there were thousands of companies across the USA using commercial electric trucks in dozens of cities. I’ve republished a book, The Electric Vehicle Handbook![]() , that goes over this in tremendous detail. Most of that book, published in 1922, describes the technology available at that time for exactly the same sort of delivery van, and in one chapter goes over the economics. Technology has of course improved a lot in the intervening 100 years, but the economics are exactly the same.

, that goes over this in tremendous detail. Most of that book, published in 1922, describes the technology available at that time for exactly the same sort of delivery van, and in one chapter goes over the economics. Technology has of course improved a lot in the intervening 100 years, but the economics are exactly the same.

For example, the 1922 equivalent of FedEx, American Railway Express Agency, handled rapid package delivery across the USA. Packages were sent via train from one city to another. For the “last mile delivery” tasks, the company used electric trucks. Other scenarios were bakeries or dairies that ran delivery routes using electric trucks.

The primary competition of that time was horse-drawn trucks. Operational costs for such trucks include veterinarian bills and feed. Then, as now, the primary cost for delivery companies was the operational cost of their vehicle fleet. The cost comparisons look very similar to the table ELMS presents in its investor slide deck.

Customization

It is common for commercial vehicles to be customized for the needs of each customer. For example, delivering frozen items requires a refrigeration unit, while mobile technicians require equipment storage lockers and racks on the top to carry ladders, and food trucks require openable windows and cooking equipment.

The ELMS slide deck shows vans customized for each need. The common practice is for 3rd party companies to handle such customization. With competitor vehicles, that requires a second step. The vehicle is first delivered to the customizer, where the custom equipment is installed, and then the vehicle is delivered by the customizer to the customer.

ELMS is looking to integrate customizer teams into their factory, so that customization happens in the ELMS factory. This is claimed to improve delivery time, provide a single warranty to the end customer, and reduce costs.

Summary

ELMS company management is drawn from several automotive companies. Each brings to the table at least 25 years of industry experience.

The vision is clear, that there is a large addressable market for electric delivery vans, and that their solution should prove attractive. Over time they expect to develop other vehicles, including larger vans and trucks.

By 2023 their goal is to sell vehicles not just in the USA, but in China and the European Union. By 2025 they may have solid-state batteries for autonomous vehicles and operate a “Mobility as a Service” offering. Big goals.

- Is there enough Grid Capacity for Hydrogen Fuel Cell or Battery Electric cars? - April 23, 2023

- Is Tesla finagling to grab federal NEVI dollars for Supercharger network? - November 15, 2022

- Tesla announces the North American Charging Standard charging connector - November 11, 2022

- Lightning Motorcycles adopts Silicon battery, 5 minute charge time gives 135 miles range - November 9, 2022

- Tesla Autopilot under US Dept of Transportation scrutiny - June 13, 2022

- Spectacular CNG bus fire misrepresented as EV bus fire - April 21, 2022

- Moldova, Ukraine, Georgia, Russia, and the European Energy Crisis - December 21, 2021

- Li-Bridge leading the USA across lithium battery chasm - October 29, 2021

- USA increasing domestic lithium battery research and manufacturing - October 28, 2021

- Electrify America building USA/Canada-wide EV charging network - October 27, 2021