A car-oriented news blog wrote an article claiming that Toyota “spurred a movement toward automotive electrification that can be traced directly to modern EVs like the Tesla Model Y and Rivian R1T“, and claims that Toyota is making a huge misstep, huge mistake in other words, in not currently selling a battery electric vehicle. The second point I agree with, but the first just does not fit with actual history. It is the duty for those of us who lived through this piece of history to make sure and tell the story so that our descendants know what actually happened.

The claim is made that Toyota spurred this movement towards electric cars, because Toyota released the Toyota Prius in 1997. The article author conveniently forgets that Honda released their own Hybrid, the Honda Insight, at the same time.

In 1997 the first wave of the ZEV mandate cars was in full swing. You could lease a GM EV1 from Saturn dealerships, and the Gen1 Toyota RAV4 EV, the Ford Ranger EV, the electric Chevy S10 pickup, the Honda EV+, etc. Toyota was responsible for a small corner of this story, the Gen1 RAV4 EV, which had a bit part in Who Killed the Electric Car.

To Toyota’s credit, the Gen1 RAV4 EV is the primary survivor of the first wave of ZEV Mandate cars. There are a few Ranger EV’s still around, but it is far more likely to see a Gen1 RAV4 EV than a Ranger EV.

First Wave ZEV Mandate cars

I should explain what I mean by “First Wave ZEV Mandate” car. The ZEV Mandate was California’s plan to force the car companies to make zero emissions vehicles (ZEV meaning Zero Emission Vehicle). The mandate was enacted in the early 1990’s as a response to air pollution problems in California. Back in the 1960’s it was becoming clear to Los Angeles residents that cars were causing a terrible pollution problem. I’ve heard that the mountains ringing the Los Angeles basin were jokingly referred to Hertz Rent-a-Mountains because on most days the smog was so thick you couldn’t see the mountains.

<DIGRESSION> Protests by citizens caused California to form CARB, or the California Air Resources Board, empowered to regulate air quality in California. California has a long standing precedence in regulating its own air quality, and setting its own air quality requirements. So when the Trump Administration EPA demands that California stop doing this, they are going against DECADES of history. </DIGRESSION>

In the early 90’s, CARB had gotten enough data to back up a demand that car companies start shifting their car production to ZEV vehicles. The requirement was that the car companies, in order to continue having the right to sell cars in California, must sell a modest number of ZEV’s in California.

Because it was a requirement, this became known as the ZEV Mandate.

In response to the mandate the car companies developed and started selling (or leasing) the cars listed above.

Hacktivists and the DIY Prius Plug-in

Some of us who wanted electric cars in 2002 or thereabouts took it upon ourselves to develop open source plans to convert a Toyota Prius to a Prius Plug-in.

This is an example from 2007. Every year the Silicon Valley Electric Auto Association held an “EV Rally”, and by 2007 it had grown large enough to require the parking lot at Palo Alto High School. When I first began attending that rally, it was held in an out-of-the-way corner of the Stanford Univ campus, but in 2001/2002 it was a significant enough event to draw GM and Honda and Nissan and Toyota to make major presentations of the ZEV Mandate cars. All that was gone by 2007, and instead in that time frame the EV Rally was almost solely attended by enthusiasts.

CalCars attended for a couple years with their Prius Plug-in conversions. While I have clear memory of seeing them at the event, I did not interact with them at the time and do not have pictures. I have since interacted with several people associated with the project.

This was an effort undertaken by many DIY electric vehicle enthusiasts, and I believe that CalCars played the largest role. One result is the EAA Plug-in Hybrid website which documented all kinds of data related to converting a Toyota Prius to be a Plug-in Hybrid http://www.eaa-phev.org/wiki/Main_Page![]()

At the time Toyota was selling as many Prius’s as it could make but did nothing to further the cause of electric cars. The Prius, in fact, spawned a phrase spoken by electric vehicle fans of the time — “It’s not electric unless you can plug it in”.

Despite Toyota’s best effort to say the Prius was a Hybrid Electric Vehicle, it was not designed to be plugged-in and therefore all the electric drive train power comes from burning gasoline.

Toyota had nothing to do with developing the open source Prius Plug-in. What I take as a sign of Toyota’s opinion happened when I was at a car show, probably in 2010. In the Toyota booth, I was talking with a Toyota representative, who was eagerly urging me to come see the Prius. I asked the person when would Toyota come out with their own Prius Plug-in, and the person turned cold as ice and walked away.

Toyota and Tesla and NUMMI

The one thing of significance which Toyota did to “spur the electrification craze” would have to be selling the NUMMI plant to Tesla Motors.

Until about 2008, GM and Toyota jointly operated the NUMMI plant. This car factory in Fremont CA at the time had a capacity of producing 450,000 cars per year. But the economic downturn in 2008-9, and GM’s bankruptcy at that time, doomed GM’s involvement with the factory. And Toyota probably could not afford to keep it running on its own, and shut down the factory.

The deal was structured such that Tesla paid Toyota $40 million for the factory site, and Toyota made a similarly sized investment in Tesla. Hence, Toyota gave the money to Tesla with which to buy the NUMMI factory.

Today Tesla is on the verge of building 500,000 electric cars per year. What enabled todays result is the fact that Toyota gave the NUMMI factory to Tesla. At the time Tesla was producing a few Roadsters, and promising the Tesla Model S, and we all scratched our heads over what Tesla would do with such a large factory. Now we know.

Tesla’s “affordable mass market electric car” required owning multiple large factories.

The Gen2 Toyota RAV4 EV

The other result from the Toyota/Tesla joint venture — the Gen2 Toyota RAV4 EV – is not an example of Toyota spurring the electrification craze.

Announced at the same time, Toyota and Tesla teamed up on producing the Gen2 RAV4 EV. This car was unveiled at EVS26 in 2012. By the time of the unveiling, it was clear that Tesla intended to produce exactly 2,600 of these cars and that was it.

The cars were produced at the same factory in Ontario where the RAV4 EV is produced. Most telling is that by the time it was announced, Toyota announced the next generation of the RAV4 platform, and there were zero plans to move the RAV4 EV to that platform.

Toyota needed ZEV points in order to keep selling cars in California. Therefore Toyota needed to produce exactly 2,600 RAV4 EV’s to get enough points to keep selling cars in California. And that was that.

Toyota later sold its stake in Tesla Motors.

AC Propulsion, GM EV1, Tesla Motors

There was another car from the first wave ZEV Mandate cars that made a more significant impact on the current wave of electric vehicles than anything Toyota ever did.

Toyota had nothing to do with this car. It was a project run jointly by General Motors, and Aerovironment, using a drive train developed by AC Propulsion.

The GM EV1 was such a fabulous car that it inspired folks to create a movie about it after GM canceled the EV1 program.

The drive train was also used in the tZero electric sports car developed by AC Propulsion. THAT car was later seen by the original founders of Tesla Motors, and was the car which proved to Tesla’s founders that an exciting electric sports car was feasible. They licensed drive train technology from AC Propulsion, using it in the Tesla Roadster.

Tesla and the budding electric vehicle craze

Clearly the existence of Tesla Motors has done a lot more to build excitement about electric vehicles than Toyota ever dreamed of.

Tesla’s founders knew that to make a significant market for electric cars, that a car had to exist which would blow up all the electric car stereotypes — slow, boring, ugly, short range, etc.

Hence, since its founding Tesla Motors has built fast, good looking, exciting electric cars with long range. The result is that customers are flocking to Tesla.

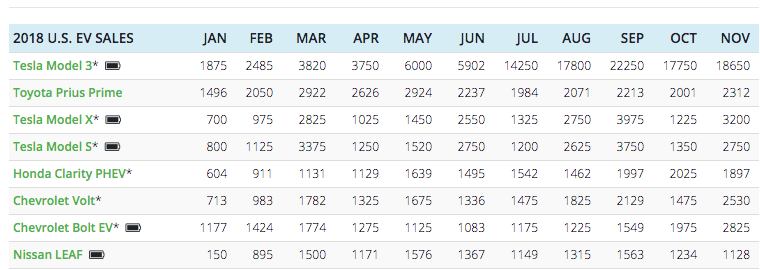

This is sufficient proof for that statement – in 2018, Tesla outsold the next best selling plug-in vehicle by nearly a 10x factor. Tesla had three of the top 5 selling electric cars in 2018. US Sales figures.

Tesla is so deeply ingrained in most peoples minds that on Quora most of the questions about electric cars say “Tesla” rather than “Electric Car”.

Toyota had nothing to do with this result other than selling Tesla a disused factory.

- The USA should delete Musk from power, Instead of deleting whole agencies as he demands - February 14, 2025

- Elon Musk, fiduciary duties, his six companies PLUS his political activities - February 10, 2025

- Is there enough Grid Capacity for Hydrogen Fuel Cell or Battery Electric cars? - April 23, 2023

- Is Tesla finagling to grab federal NEVI dollars for Supercharger network? - November 15, 2022

- Tesla announces the North American Charging Standard charging connector - November 11, 2022

- Lightning Motorcycles adopts Silicon battery, 5 minute charge time gives 135 miles range - November 9, 2022

- Tesla Autopilot under US Dept of Transportation scrutiny - June 13, 2022

- Spectacular CNG bus fire misrepresented as EV bus fire - April 21, 2022

- Moldova, Ukraine, Georgia, Russia, and the European Energy Crisis - December 21, 2021

- Li-Bridge leading the USA across lithium battery chasm - October 29, 2021